Isaiah 7:14 and the Almah: Immanuel, Covenant Faithfulness, Sign-Acts, and the Incarnation

Explore Isaiah 7:14 through covenant theology, prophetic sign-acts, and the almah/parthenos debate, clarifying immediate and messianic readings for Advent.

I'm preaching on Isaiah 7:14 this Sunday for the first week of Advent. The passage sits at the intersection of covenant theology, prophetic sign-acts, and the doctrine of the incarnation. Most people know it as a Christmas proof-text. That's not wrong, but it barely scratches the surface.

Divine Initiative in Covenant Crisis

Isaiah 7:14 emerges from the Syro-Ephraimite crisis around 735 BC. Syria and Israel have formed an anti-Assyrian alliance and are pressuring Judah to join. When Ahaz refuses, they march against Jerusalem to forcibly replace him with a puppet king who will cooperate.

This isn't just a political crisis. It's a direct threat to the Davidic covenant. God promised David an everlasting dynasty. Now two regional powers are plotting to end that dynasty by force. The theological question isn't whether Judah will survive militarily. It's whether God's covenant word is reliable.

Ahaz responds by considering an alliance with Assyria. This would make Judah a vassal state and introduce Assyrian cultic practices into Jerusalem. It's covenant apostasy dressed up as realpolitik.

Isaiah confronts him with a prophetic offer: ask God for a sign confirming his covenant faithfulness. Any sign. Heaven or earth. Ahaz refuses under the pretense of piety, but the real issue is that he's already made his decision. He doesn't want divine confirmation because he's not planning to trust divine promises.

So God gives a sign anyway. "Therefore the LORD himself will give you a sign."

The grammar is emphatic. The subject is Yahweh, not the prophet. This isn't Isaiah's word. It's God's direct covenant intervention in a moment when the Davidic promise appears to be collapsing.

The Sign-Act Genre

The verse reads: "Behold, the young woman is with child and will bear a son, and she shall call his name Immanuel."

This is prophetic sign-act literature. Isaiah uses his own children as living prophecies in this section. Shear-jashub in 7:3 means "a remnant will return." Maher-shalal-hash-baz in 8:3 means "swift is the booty, speedy is the prey." These aren't random baby names. They're incarnated theological messages.

The sign here follows the same pattern. A child will be born whose very existence and name function as a prophetic word. The name Immanuel means "God with us." The child himself becomes a walking declaration of divine presence.

The immediate referent appears to be a child born in Isaiah's own time. The prophecy includes a temporal marker: before this child knows to refuse evil and choose good, the threatening kings will be gone. That's roughly three to five years. The sign has near-term, verifiable fulfillment.

This matters for understanding prophetic literature. The sign wasn't given to Ahaz about something 700 years in the future. It addressed his immediate crisis with a concrete, datable promise. God is present now, not just eventually.

The Lexical Question and Its Theological Stakes

The Hebrew word is almah (עַלְמָה). It appears nine times in the Hebrew Bible and consistently denotes a young woman of marriageable age. The semantic range includes but does not require virginity. The more specific Hebrew term for virgin is bethulah (בְּתוּלָה), which Isaiah could have used but didn't.

In the Septuagint, produced around 200 BC, Jewish translators rendered almah as parthenos (παρθένος). This Greek term is unambiguous: it means virgin. This translation choice has massive implications for how the verse gets read in Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity.

Matthew quotes the Septuagint version in Matthew 1:23, explicitly applying the parthenos reading to Jesus' virginal conception. This isn't Matthew misreading the Hebrew. He's working within the established Greek translation tradition and recognizing a typological pattern that reaches its climax in the incarnation.

Here's what matters theologically: the immediate historical referent in Isaiah's context didn't require virginal conception. The sign worked for Ahaz as a normally-conceived child whose name proclaimed God's presence. But the Septuagint translators saw something in the text that allowed for the parthenos rendering. And Matthew, under inspiration, recognizes that what was possible in the immediate context finds its ultimate fulfillment in the impossible: a virgin conceiving without human agency.

I encountered this directly while building the Anselm Project Bible. The AI kept defaulting to traditional renderings because it recognized the pattern. When I forced strict lexical translation, it produced "young woman." But the text's canonical trajectory—from almah to parthenos to Matthew's fulfillment claim—demonstrates how prophetic literature can carry both immediate and ultimate referents without contradiction.

The virgin birth isn't imposed on the text. It's the ultimate realization of what the sign-act genre was always capable of expressing: God's direct intervention in human history through unexpected, covenant-preserving means.

Typology and the Unity of Redemptive History

The relationship between the immediate sign and the messianic fulfillment isn't arbitrary. It's typological. Typology assumes that God works in patterns across redemptive history, with earlier events establishing forms that later events fill with fuller meaning.

The immediate sign in Isaiah's day had these characteristics: a child born in a time of covenant crisis, a name declaring God's presence, a promise that God would preserve the Davidic line despite overwhelming opposition.

The ultimate fulfillment in Christ maintains those exact characteristics but amplifies them. A child born when the Davidic line appears exhausted and politically irrelevant. A name declaring God's presence, but now God's presence is ontologically realized in the hypostatic union. A promise that God will preserve his covenant, but now through resurrection and eternal reign rather than temporary military deliverance.

The typological reading doesn't negate the historical fulfillment. It recognizes that the historical fulfillment was always pointing beyond itself. The near-term sign worked precisely because it participated in a larger pattern that would reach definitive expression in the incarnation.

This is how biblical prophecy functions. It's not merely predictive. It's pattern-setting. God establishes covenant patterns in history, and those patterns recur with increasing intensity until they reach their telos in Christ.

Isaiah's immediate audience needed assurance that God was with them in 735 BC. They got it. The child was born, the name was proclaimed, the threat dissolved within a few years. But that assurance itself pointed to the ultimate Immanuel who would be God-with-us not by proclamation but by personal presence.

The Gospels don't impose messianic meaning on a non-messianic text. They recognize the messianic trajectory already present in how Isaiah uses sign-children, covenant promises, and divine presence language throughout his prophecy. Isaiah 9:6-7 and 11:1-10 make explicit what 7:14 implies: the coming king who will embody God's reign.

Matthew sees Jesus as the fulfillment not just of this isolated verse but of Isaiah's entire theological vision of how God will restore his people through a Davidic king who carries divine prerogatives.

Immanuel and the Already-Not Yet Tension

Advent liturgy positions us in the same tension that characterizes all of redemptive history post-incarnation. Christ has come. The Immanuel promise found its definitive historical realization in Bethlehem. But we still await the consummation when God's presence will be fully, finally, and visibly manifested in the new creation.

This isn't just a liturgical exercise. It's the theological structure of Christian existence. We live between the times. The kingdom has been inaugurated but not consummated. The Spirit has been poured out but we still groan awaiting the redemption of our bodies. Christ has come but we still pray "Come, Lord Jesus."

Isaiah 7:14 functions in exactly this way. The immediate sign was given and fulfilled. The ultimate sign was given and fulfilled in the incarnation. But the final manifestation of God dwelling with his people awaits Revelation 21:3, when the tabernacle of God is with humanity in the eschaton.

The name Immanuel bridges all three horizons. God was with Judah in the eighth century BC. God was with humanity in the incarnation. God is with the church by the Spirit. God will be with the redeemed in the new creation. The theological content of the name doesn't change, but its mode of realization intensifies across redemptive history.

Advent preaching on this text should resist collapsing these horizons. We're not just remembering what God did. We're not just anticipating what God will do. We're recognizing what God is doing now as Immanuel by the Spirit, based on what he accomplished definitively in Christ.

The doctrine of divine presence isn't abstract. It has covenantal, christological, pneumatological, and eschatological dimensions. Isaiah 7:14 touches all of them.

Faith, Fear, and Divine Sovereignty

Ahaz's crisis reveals a perennial theological problem: the relationship between divine sovereignty and human agency in political contexts.

The covenant promised David an everlasting dynasty. That's an unconditional divine commitment. But Ahaz faces a concrete military threat that could end the Davidic line within months. How should covenant theology interact with geopolitical realities?

Ahaz opts for pragmatism. He seeks Assyrian protection, which means accepting vassal status and syncretistic religious practices. From a political standpoint, it's rational. Assyria is the superpower. An alliance secures survival.

But Isaiah's prophetic word reframes the entire situation. The real question isn't whether Assyria can protect Judah. It's whether God will keep his covenant promise. The sign of Immanuel directly addresses this. God's presence guarantees the Davidic line regardless of military probabilities.

This creates a theological test. Will Ahaz trust God's covenant word over visible political realities? Will he order his decisions based on divine promise or human calculation?

His refusal to ask for a sign isn't piety. It's doubt masquerading as humility. He doesn't want confirmation of God's faithfulness because he's already chosen a different foundation for security.

The theological issue here isn't whether human agency matters. God works through means. Political wisdom has its place. But when political expedience requires covenant compromise, it stops being wisdom and becomes practical atheism.

The Immanuel sign confronts that atheism. God is not absent from history. He's not indifferent to covenant threats. His presence is the decisive reality, and that presence demands a faith response that orders all other decisions.

This has direct application to how Christians navigate politics. We're not called to political quietism. But we're also not called to secure God's purposes through ungodly means. The kingdom of God doesn't advance through covenant betrayal, even when betrayal looks strategically necessary.

The test is always the same: do we believe God is actually present and active, or are we functional deists who talk about sovereignty on Sunday but operate as secularists Monday through Saturday?

Incarnational Presence and Covenant Theology

The theological move from "God with us" as a covenant assurance to "God with us" as incarnational reality is staggering.

In Isaiah's context, divine presence meant God's covenantal faithfulness, his active preservation of the Davidic line, his intervention in Israel's crises. It was real presence but mediated presence. God was with his people through word, through sign, through providential action in history.

The incarnation collapses the distance between God and humanity. The Word becomes flesh. Divine nature assumes human nature in the person of Christ. God is not just with us in the sense of being near or active on our behalf. God is with us in the sense of sharing our nature, our experience, our condition.

This is why Hebrews 2:14-18 makes such a big deal about the incarnation. Christ had to become truly human to be a merciful and faithful high priest. The solidarity required ontological union, not just sympathetic presence from a distance.

The Immanuel promise reaches its theological climax here. What began as covenant assurance ("I won't abandon you") becomes ontological reality ("I am one of you"). The typological pattern finds its antitype. The sign-child points to the God-man.

But the incarnation doesn't exhaust divine presence. Pentecost extends it. The same Spirit who overshadowed Mary, who anointed Jesus, who raised him from the dead, now indwells believers. Immanuel isn't just a historical person. It's a present pneumatological reality.

This creates the strange tension of Christian existence. We confess Christ's bodily absence ("he ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father") and simultaneous presence ("I am with you always, even to the end of the age"). The resolution is pneumatological. The Spirit makes Christ present to the church until the parousia.

So the Immanuel promise moves from covenant assurance (Isaiah) to incarnational presence (Gospels) to pneumatological indwelling (Acts-Revelation) to eschatological consummation (Revelation 21). The theological content expands while maintaining continuity. God's being-with-us intensifies across redemptive history without changing its essential nature.

Homiletical Strategy

The sermon needs to accomplish several things simultaneously. It has to establish the historical context without losing the congregation in eighth-century geopolitics. It has to handle the lexical question honestly without getting trapped in translation debates. It has to demonstrate typological fulfillment without allegorizing away the historical referent. And it has to apply incarnational theology to contemporary life without reducing "God with us" to therapeutic presence.

I'm structuring it around three movements: Promise, Provision, Presence.

The Promise section establishes divine initiative. God speaks into the covenant crisis. He offers a sign when the king refuses to ask. The theological weight is on Yahweh as subject. The LORD himself will give you a sign. This isn't prophetic speculation. It's divine self-commitment.

The Provision section unpacks the sign itself. A child will be born. The naming will function as theological proclamation. The near-term fulfillment addresses Ahaz's immediate crisis. The typological structure points forward to ultimate fulfillment. The lexical question about almah gets addressed here, showing how the Septuagint's parthenos enables Matthew's use without negating Isaiah's immediate context.

The Presence section drives toward the incarnation and then toward pneumatological application. Immanuel isn't just a name. It's a reality that unfolds across redemptive history. Covenant presence becomes incarnational presence becomes pneumatological indwelling becomes eschatological consummation. The sermon should help people see the theological trajectory without losing the historical anchor.

The application focuses on what it means to trust divine presence over political calculation. Ahaz's failure provides the negative example. He had the promise, refused the confirmation, and compromised the covenant. The positive example is Mary's fiat. She receives the Immanuel promise and responds with trust despite the impossibility.

The goal isn't to make people feel warm about God being near. The goal is to confront functional deism and call people to order their entire lives around the reality of divine presence. That looks like something concrete. It changes decision-making. It reframes suffering. It subordinates political anxiety to covenant confidence.

This is Advent theology. We're not just remembering past comfort. We're being trained to trust the God who has proven his faithfulness in history, who became flesh to secure our redemption, who dwells with us by the Spirit, and who will consummate all things when Christ returns.

The Share Gallery has other studies working through similar theological questions if you want to see how this kind of biblical theology gets worked out across different texts. If you want to explore the Hebrew and Greek terminology yourself, the biblical lexicon breaks down key terms like almah, parthenos, and other concepts central to understanding prophetic literature. The AI-generated report this post is based on runs to about 80 pages of analysis, which gives you a sense of how much depth is available when you actually dig into the text.

Isaiah 7:14 isn't just a Christmas verse. It's covenant theology, Christology, pneumatology, and eschatology compressed into one prophetic sentence. That's what makes it worth preaching well.

God bless, everyone.

Related Articles

Isaiah 26:3-4 Explained: Hebrew 'Peace, Peace' (Shalom Shalom) and the Everlasting Rock

Explore Isaiah 26:3-4: a Hebrew exegesis of "shalom shalom" and the everlasting Rock, showing how tr...

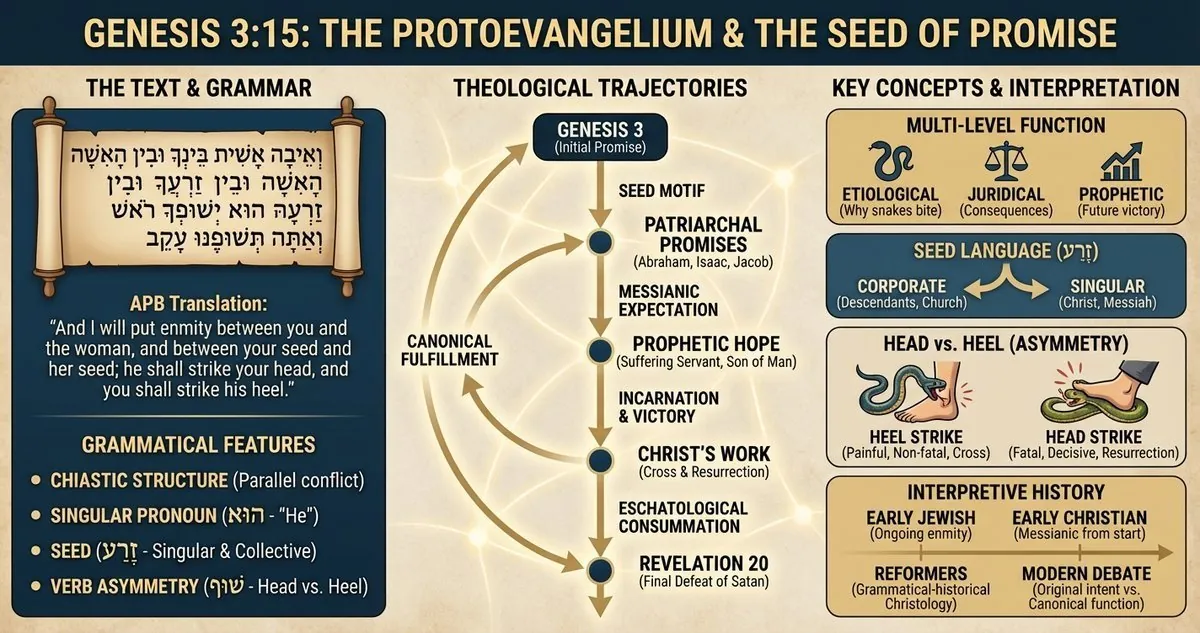

Genesis 3:15 Explained: Protoevangelium, Hebrew Grammar, and Messianic Seed

Explore Genesis 3:15 as the protoevangelium with grammatical, theological, and canonical readings th...

When Speech Betrays You: Peter's Denial and the Anatomy of Failure

Study Peter's denial in Matthew 26:69-75: an exegetical exploration of prophecy fulfillment, honor-s...